Editor note: This is the 3rd and final installment of the Glenn Hoplin reminiscences, this describing living through the depression years in Lowry.

The stock market crashed in 1929 and it became difficult to provide for 11 people. [Editor note: Ole, Esther, 7 children, father Carl Nelson, brother Dave Nelson. Father Nils Hoplin died in 1927].

The Depression of the 30’s was a lesson in survival. During those years, most of the payments on the Sogaarden note were not made. Had this mortgage been held by a financial institution, we would certainly have suffered foreclosure. [Editor note: In 1927, Ole Hoplin borrowed $7500 from the Sogaarden brothers to build the home at 304 Drury Ave.]

Many attempts were made by the Roosevelt administration to prime the economic pump – an alphabet soup of programs: WPA, PWA, NRA, CCC to name but a few. Nothing seemed to significantly improve the economy until 1939 and the war in Europe, bringing people to work producing war materials. The government programs provided money for people to exist in manner people today cannot imagine. What is called poverty today would have been deemed extreme luxury during the depression. The Hoplin family survived the depression in large degree to the generous credit arrangements of McIver’s Store and Martin & Peter Sogaarden. [Editor note: The Hoplin Hardware Co. of Brandon was a victim of the depression, entering bankruptcy in the early 30’s]

The stock market crashed in 1929 and it became difficult to provide for 11 people. [Editor note: Ole, Esther, 7 children, father Carl Nelson, brother Dave Nelson. Father Nils Hoplin died in 1927].

The Depression of the 30’s was a lesson in survival. During those years, most of the payments on the Sogaarden note were not made. Had this mortgage been held by a financial institution, we would certainly have suffered foreclosure. [Editor note: In 1927, Ole Hoplin borrowed $7500 from the Sogaarden brothers to build the home at 304 Drury Ave.]

Many attempts were made by the Roosevelt administration to prime the economic pump – an alphabet soup of programs: WPA, PWA, NRA, CCC to name but a few. Nothing seemed to significantly improve the economy until 1939 and the war in Europe, bringing people to work producing war materials. The government programs provided money for people to exist in manner people today cannot imagine. What is called poverty today would have been deemed extreme luxury during the depression. The Hoplin family survived the depression in large degree to the generous credit arrangements of McIver’s Store and Martin & Peter Sogaarden. [Editor note: The Hoplin Hardware Co. of Brandon was a victim of the depression, entering bankruptcy in the early 30’s]

In 1930, Dr. Gibbon died. His widow Anna asked Ole to buy the Hudson Super Six automobile. It had a hood longer than the car body, a huge engine and an insatiable appetite for gasoline. It was equipped with puncture proof tires. The depression had hit and Anna could not get rid of the vehicle, so she told dad he had to buy it for $400. She said he owed them that. It was the only family auto owned by the family other than the 1923 Overland. It was little used because it cost so much to operate.

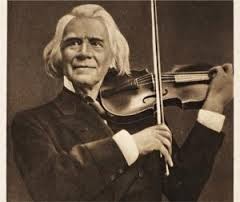

During the ‘30s in Lowry, many youngsters were taking violin lessons from Mrs. Bill Lesley. She directed an all violin orchestra of 15-20 children scratching away at most PTA meetings. Glenwood High School had an orchestra that was heavily supplied with string players from Lowry. I was one of the diligent students, practicing perhaps up to 15 minutes a day, after which I had expended so much energy and concentration I became exhausted and laid my instrument on the davenport while I rested and considered. Brother Bud entered the scene and sat on the davenport separating the neck of the violin from its body. This terminated a very promising musical career and opened the door for Ole Bull – leaving me to a plumber’s life.

|

| Dorothea Lange's classic Migrant Mother depicts destitute pea pickers in California, a mother of seven children, age 32, March 1936. |

For several years crops were poor and livestock feed scarce. Much of the grain was so short that bundles could not be made with a binder, so the grain was cut and winnowed like hay. The threshing machines were set with the blower through the barn down and the straw blown in for livestock feed. Every growing green thing was used for feed. The fences had drifts of topsoil like snow and the trash and tumbleweed collected along the fence lines. It is impossible to imagine the poverty brought by the drought and depression unless you have experienced the devastation. And to compound matters, the winter of 1936 was the coldest in record. Most people had coal burning appliances but no money to buy coal.

The drought years alone were tough, but together with the worst depression in history, it became a terrible struggle to provide just the basic needs for a family. Many families lost their farms and went to work at jobs provided by federal programs. The federal government instituted numerous programs. NRA – National Recovery Act. The CCC – Civilian Conservation Corps, a program that put young men to work with the forest service, many times working for room, board and clothing.

In 1938 city water was installed by a PWA project. The PWA – Public Works Administration created work for contractors. In this program, government contracts were issued to build infrastructures in small towns and cities. The government dictated policy and wage scales. Laborers were given 55 cents / hour. Many men were working for $1 a day. Under this program, Henry Nodland Construction of Starbuck constructed the municipal water system. The amount of the contract was so small that it’s hard to believe so much could be gotten for so little. All the 6 & 8” cast iron water mains, hydrants, a new well and well house, a 10 HP deep well turbine pump, a 100’ water tower and tank. Every joint in the cast iron mains were joined with oakum and molten lead. Ditches were dug with a huge chain digger with a belt conveyor. Backfilling was done with a drag line.

In 1938 city water was installed by a PWA project. The PWA – Public Works Administration created work for contractors. In this program, government contracts were issued to build infrastructures in small towns and cities. The government dictated policy and wage scales. Laborers were given 55 cents / hour. Many men were working for $1 a day. Under this program, Henry Nodland Construction of Starbuck constructed the municipal water system. The amount of the contract was so small that it’s hard to believe so much could be gotten for so little. All the 6 & 8” cast iron water mains, hydrants, a new well and well house, a 10 HP deep well turbine pump, a 100’ water tower and tank. Every joint in the cast iron mains were joined with oakum and molten lead. Ditches were dug with a huge chain digger with a belt conveyor. Backfilling was done with a drag line. I worked for Henry Nodland for 55 cents/hour, which was fabulous. People complained that an 18 year old kid who didn’t know anything should be paid such an outlandish amount. Most of the days were 10 hours and since I lived in town, I was asked to take care of lighting all the flares and fill them with kerosene and then extinguish them in the morning. I also rose early to light the fire under the lead pot so the molten lead was ready for the 7 AM work start. I was supposed to get an extra hour’s pay for this. For several blocks the 6”, 18’ long pipes were laid along the ditch with the bell ends reversed. These then had to be turned 180 degrees into the ditch.

|

| WPA road building in Northern Minnesota - 1933 |

The WPA - Work Progress Administration -provided jobs that built roads, parks, and public buildings. The skating rink in Lowry was constructed with a warming house that has a fireplace of native rock. The building remains to the present day, however the fireplace has been removed. The schoolhouse was shingled, all the maple flooring in the classrooms were taken up, cleaned, re-laid and sealed. The entire interior of the school was given a coat of Kalsomine. The cedar trees that lined the east side of Highway 114 were moved by the WPA from directly behind the school building. These trees had been used as enclosures for the outdoor plumbing – one for the boys and one for the girls. There were 3-4 toilets in each enclosure with access through the trees. Amazingly, every tree survived the transplant. In recent years, apartments have been constructed just east of this tree line and the shade of these trees adds to the location.

The WPA - Work Progress Administration -provided jobs that built roads, parks, and public buildings. The skating rink in Lowry was constructed with a warming house that has a fireplace of native rock. The building remains to the present day, however the fireplace has been removed. The schoolhouse was shingled, all the maple flooring in the classrooms were taken up, cleaned, re-laid and sealed. The entire interior of the school was given a coat of Kalsomine. The cedar trees that lined the east side of Highway 114 were moved by the WPA from directly behind the school building. These trees had been used as enclosures for the outdoor plumbing – one for the boys and one for the girls. There were 3-4 toilets in each enclosure with access through the trees. Amazingly, every tree survived the transplant. In recent years, apartments have been constructed just east of this tree line and the shade of these trees adds to the location. Rural electrification came to area in the late ‘30s. Dad had a master’s electrician’s license and began wiring farms all around the area. Sometimes there were two crews working, one wiring the house and the other string yard wire from the yard pole to the buildings. All the work was by hand. Holes were drilled by hand with Miller Falls Corner braces. All sawing was with hand tools. The crews became very efficient at fishing wire in old houses. It supplied the very basic needs – lights and a few outlets. People were happy with this convenience after struggling with kerosene lamps that were smelly and offered little light. The saying was “you needed to light a match to see of the lamp was burning”. However there were vastly improved forms of non-electric light, so called Aladdin Lamps. It burned kerosene, had a mantle and burned with beautiful white light.. The gasoline lantern had two mantles and a pressurized gasoline tank that had to have its generator heated with raw gasoline before the mantles would function. These lamps created a fine parts business for wicks, lamp chimneys, mantles and burners.

The commodity prices during the Depression were unbelievable low. The market was putrid. So even though the drought was broken, the suffering continued. Not until 1939 and the onset of war in Europe did the economy improve. Before the US entered the war after Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), the US supplied war materials to Great Britain under the Lend Lease program. All kinds of materials, including ships were delivered. After December 7, 1941, US industry converted completely to military production. Almost all consumer goods production shut down. Auto makers converted to tanks, airplanes, ships and other war materials. With so many men gone to fight, much of this construction work was done by women and older men.

Every generation seems compelled to tell how tough it had it. I remember Grandpa Nils telling how he worked building the railroad when he immigrated, working with a pick & shovel and wheelbarrow sixteen hours a day and a slave driver for a boss. When I look at railroad grades, I see lots of wheelbarrows of dirt. A generation later, I remember John Lind telling me “ You young whippersnappers don’t know nothing. When you’ve dragged the ground I’ve plowed, then you’ll know something.”

[Editor notes: At the height of the Great Depression in 1932-33, it is estimated that there were 16 million unemployed, a rate exceeding 30%. Extreme unemployment drove men to ride the rails in empty boxcars looking for jobs and a “hobo culture” developed. A hobo sign-language, “Hobo Marks”, developed to warn or assist men who might cross the same path. I have no evidence, but I am convinced the Ole Hoplin residence was “marked” because a continual stream of impoverished men appeared at their doorstep looking for handouts. Esther never turned anyone away, but they were never allowed to enter the house. They would eat on the back steps.]

From The Hobo Code posted by Daniel Lew 2006

The variety of messages passed between hobos is incredible. There are some basic traveling symbols such as "go this way," "don't go that way," or "get out fast." Then there's praises and warnings of the locals - "doctor, no charge," "police officer lives here, not kind to tramps," "dangerous neighborhood," "you may sleep in barn." Some of my favorites messages I've heard of are "good lady lives here, tell a hard luck story," "fake illness here," "road spoiled, full of other hobos." Hobo signs were typically drawn onto utility poles using charcoal or some other type of temporary writing material that would wash out in time with the weather. Sometimes they would write on railroad trestle abutments, outcropping rocks, or even on houses when referring to those who lived inside.]

No comments:

Post a Comment